Taste belongs to our chemical sensing system, or the chemosenses. The complex process of tasting begins when tiny molecules released by the substances around us stimulate special cells in the nose, mouth, or throat. These special sensory cells transmit messages through nerves to the brain, where specific tastes are identified.

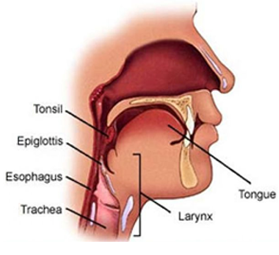

Gustatory or taste cells react to food and beverages. These surface cells in the mouth send taste information to their nerve fibers. The taste cells are clustered in the taste buds of the mouth, tongue, and throat. Many of the small bumps that can be seen on the tongue contain taste buds.

Another chemosensory mechanism, called the common chemical sense, contributes to appreciation of food flavor. In this system, thousands of nerve endings--especially on the moist surfaces of the eyes, nose, mouth, and throat--give rise to sensations like the sting of ammonia, the coolness of menthol, and the irritation of chili peppers.

We can commonly identify at least five different taste sensations: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami (the taste elicited by glutamate, which is found in chicken broth, meat extracts, and some cheeses). In the mouth, these tastes, along with texture, temperature, and the sensations from the common chemical sense, combine with odors to produce a perception of flavor. It is flavor that lets us know whether we are eating a pear or an apple. Some people are surprised to learn that flavors are recognized mainly through the sense of smell. If you hold your nose while eating chocolate, for example, you will have trouble identifying the chocolate flavor--even though you can distinguish the food's sweetness or bitterness. That is because the distinguishing characteristic of chocolate, for example, what differentiates it from caramel, is sensed largely by its odor.